The maternal health crisis in the United States

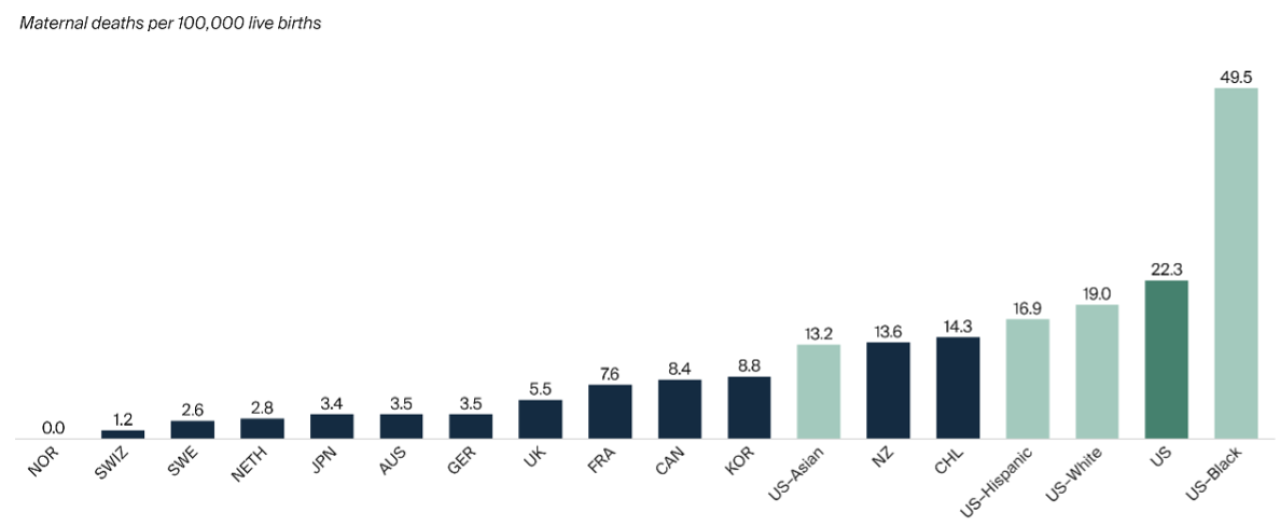

In the past 50 years, the United States healthcare industry has experienced an explosion of innovation. New technologies and modern methods of practicing medicine have improved treatment delivery and patient outcomes. Despite these positive changes, maternal and child health have not seen the same improvements. In 2022, the United States had the highest maternal mortality rate among high-income countries, with the mortality rate among Black mothers outpacing all other racial groups in the United States compared to other countries.1

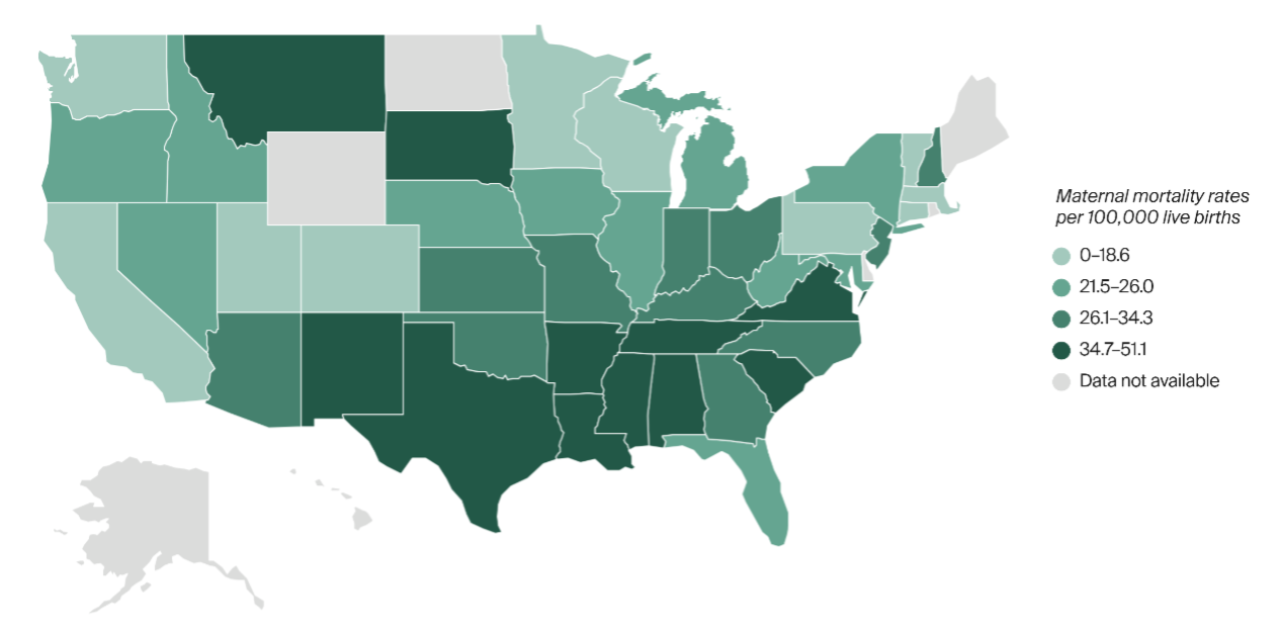

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) defines maternal death as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of [the conclusion] of pregnancy.”2 The availability of resources and care for pregnant women and new mothers heavily influences maternal mortality and child health outcomes. In the U.S., the maternal mortality rate varies and is highest in the Mississippi Delta region, which can be attributed to a lack of accessible and acceptable obstetric care, insured care, and postpartum depression screening in parts of these states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee).3

Maternal mortality is just one of the many indicators of the maternal health crisis and infant healthcare needs in the U.S. Other morbidities, such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, and mental health disorders increase the risk of health issues, ranging from emergent to chronic, for both the mother and child. These health issues result in significant and preventable consequences that stretch beyond the widely acknowledged 6-to-8-week postpartum period.4 Included in those consequences are medical and nonmedical costs; when combined, these implicate larger societal costs to reckon with.

Improving collaboration across siloed systems

The traditional siloed approach to maternal and child healthcare hinders cohesive system collaboration. Ensuring that mothers and children receive adequate and equitable care is not the sole responsibility of any one system or agency, but rather, this task is shared by a wide range of professionals.

A great opportunity for care alignment is present across the following key systems and their mechanisms of service delivery:

- Substance use: Supporting the needs of mothers with substance use disorders (SUD) and their newborns by providing appropriate treatment and support options.

- Mental health: Supporting mothers with postpartum depression (PPD), anxiety, and other mental health conditions, which may result in various complications for the mother and child in the postpartum period.

- Physical health: Ensuring consistent prenatal and postpartum checkups for early detection of common complications, and for monitoring of the mother and newborn’s health status.

- Child welfare: Providing safe and healthy home environments with adequate support for children through interventions and in-home services.

- Criminal justice: Supporting incarcerated mothers throughout the pregnancy and postpartum period with specialized care to account for increased risk of mental health crises and infectious diseases.

Across these systems, there needs to be a holistic and integrated approach to how care is delivered to mothers and their children. Social determinants of health (SDOH) must also be taken into consideration, which includes access to healthcare, housing, employment, food security, socioeconomic status, education, and social support.

Collaboration between state and local government agencies that support these areas could help reshape the landscape of maternal health. Ideally, this would include understanding available data, developing shared goals, providing funding, and offering expertise between agencies.

Prioritizing data and outcomes

Understanding data is crucial for improving maternal and child health. It identifies pressing health issues, informs policy and program development, and allows for monitoring and evaluation of health interventions. Data also aids in efficient resource allocation, promotes equity by addressing health disparities, and provides a foundation for research and innovation. Accurate data collection and analysis enables informed decision-making, enhances healthcare quality, and ultimately, saves lives.

Physical health outcomes, and data such as maternal and infant morbidity/mortality rates, low birth weight, and preterm birth rates, have dominated the data collection process. This is largely due to the easy accessibility of this information by healthcare providers across the country. However, outcomes not directly connected to physical health are essential as well. These outcomes serve to develop an understanding of the maternal and child health population, which is a necessary foundation for meeting their needs.

This can include screening for maternal mental health disorders (such as postpartum depression), tracking the rate of follow-up appointments post-screening, monitoring the access to behavioral health services, and tracking the availability of workforce training to respond to behavioral health crises. These outcomes can be difficult to measure and may require a complete evaluation of existing data collection systems to incorporate holistic and culturally appropriate approaches.

Blueprint for addressing the maternal health crisis

The White House’s “Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis”5 was developed in June 2022, reflecting the federal government’s recognition of the urgent need to address maternal health disparities and improve outcomes for all mothers and children in the United States.

There are 5 significant points worth highlighting here that are critical to effectuate change.

- Increase access to and coverage of comprehensive high-quality maternal health services, including behavioral health services

This requires exploring the expansion of comprehensive health insurance coverage and access to quality health care during pregnancy, and for a year after birth. - Ensure that those giving birth are heard and are decision-makers in accountable systems of care

It is critical that pregnant women are directly engaged in decision-making about their healthcare. Providers must listen to the voices of the individual in order to better understand the life circumstances impacting their health. A trusting partnership between women and their healthcare providers creates opportunities for improved health outcomes for mothers and their children. - Advanced data collection, standardization, transparency, research, and analysis

Data collection and analysis are necessary to support informed decision-making regarding services needs and improvement. Standardizing the collection process enables greater efficiency and transparency, which can translate to improved collaboration among government agencies. Solutions to address the maternal health crisis must be built by identifying opportunities for intervention and improvement, based on an understanding of all available data. - Expand and diversify the perinatal workforce

The health care capacity is not sufficient in many areas of the United States. Physician needs are an important part of the current resource crisis, but solving the maternal health crisis has to extend beyond a plan focusing on physician retention and practice improvement.

A comprehensive perinatal workforce needs to include other healthcare professionals and community health workers such as doulas, midwives, home health aides, and additional supports who play a pivotal role in service delivery during pregnancy, labor, and postpartum. Their roles support tailored and holistic healthcare that is culturally responsive to patients’ unique needs and situations. Healthcare workers who can identify with the populations they serve are able to better understand their patients’ backgrounds, enhancing patient experiences and improving health outcomes. - Strengthen economic and social supports for people before, during, and after pregnancy

Improving outcomes during pregnancy cannot occur without ensuring basic needs are met. This includes safe and adequate housing, sufficient healthy food, economic stability, and other social supports.

Although the Blueprint emphasizes the need for collaboration across health and human services entities and the development of data-driven, realistic strategies for counties and states, significant work still needs to be done to create solutions.

How CAI can help public agencies search for solutions

The issue of the maternal health crisis is complex, and a targeted approach is required to address the problems that often arise. Our consulting professionals have decades of experience working with state and local health and human services government entities, service providers, community partners, and other stakeholders. This equips us with the expertise to support maternal and child health program implementation and improvements, as well as to guide relationships, partnerships, budgets, and programs.

In parts 2 and 3 of this maternal health series, we will explore these topics through the lens of collaborative processes, successful partnerships, funding opportunities, data quality review and enhancements, and guidance on program implementation.

Interested to learn more? Fill out the form below to dive deeper and discuss how CAI can support your agency or department.

Endnotes

- Munira Z. Gunja, Evan D. Gumas, Relebohile Masitha, Laurie C. Zephyrin. “Insights into the U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis: An International Comparison.” The Commonwealth Fund. June 4, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison. ↩

- National Center for Health Statistics. “Detailed Evaluation of Changes in Data Collection Methods.” Center for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/maternal-mortality/evaluation.htm. ↩

- Sara R. Collins, David C. Radley, Shreya Roy, Laurie C. Zephyrin, Arnav Shah. “2024 State Scorecard on Women’s Health and Reproductive Care.” The Commonwealth Fund. July 19, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/scorecard/2024/jul/2024-state-scorecard-womens-health-and-reproductive-care. ↩

- Sasigant So O’Neil, Isabell Platt, Divya Vohra, Emma Pendl-Robinson, Eric Dehus, Laurie C. Zephyrin, Kara Zivin, “Societal cost of nine selected maternal morbidities in the United States.” Plos One. October 26, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275656. ↩

- The White House. “The White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis: Two Years of Progress | the White House.” The White House, 10 July 2024. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/07/10/the-white-house-blueprint-for-addressing-the-maternal-health-crisis-two-years-of-progress/. ↩